Helping virtual cycling belong on the global stage

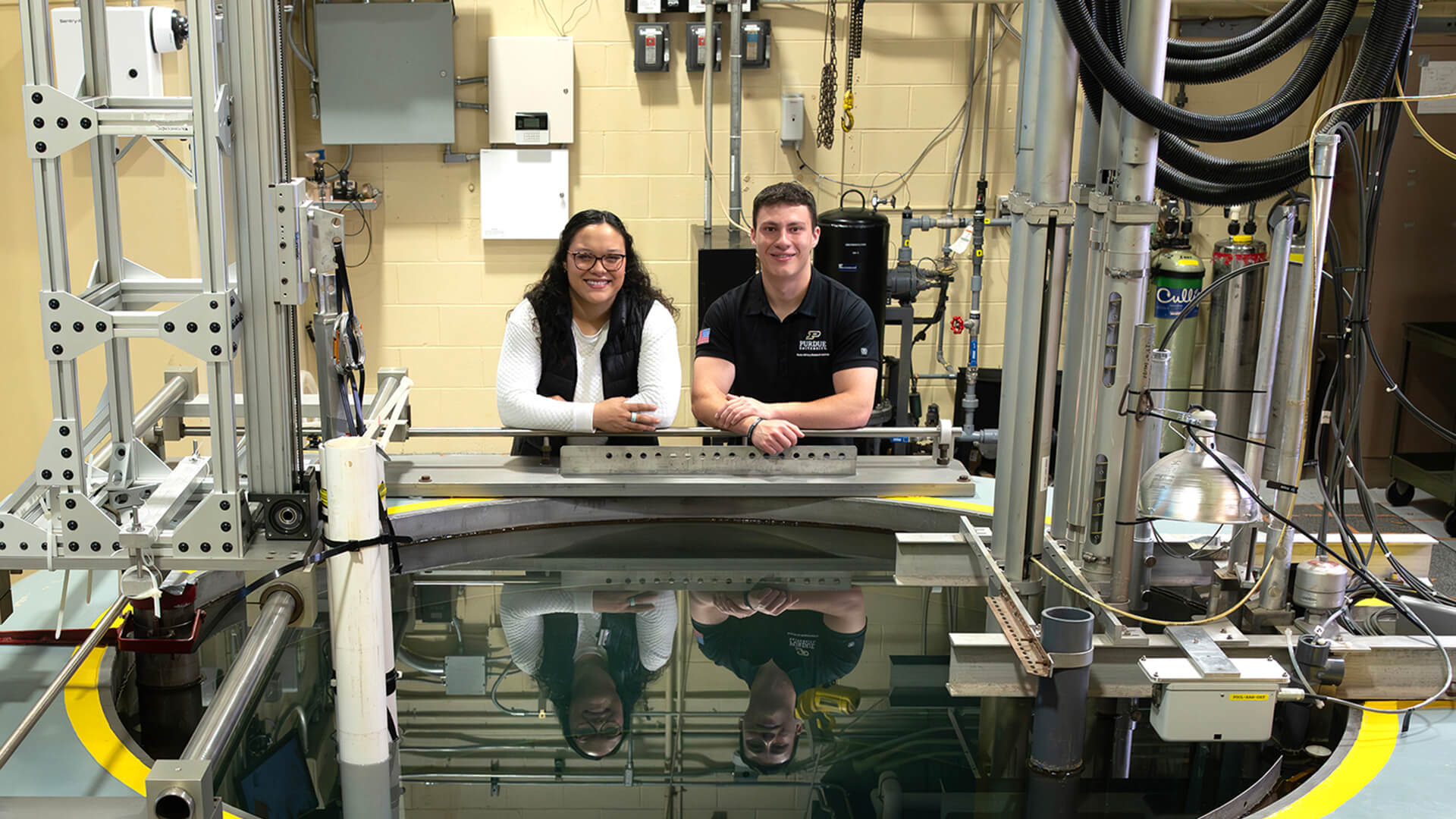

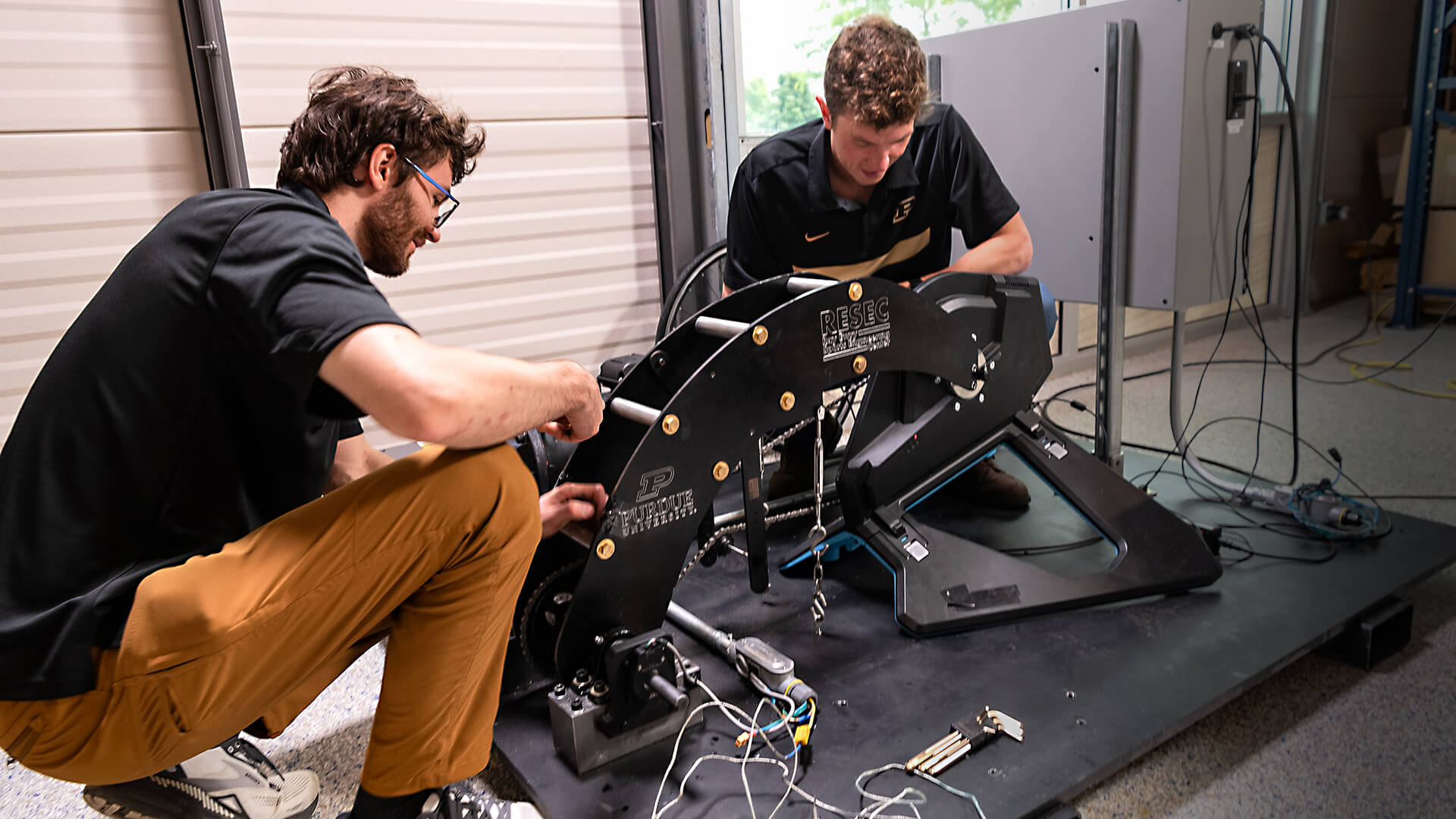

Patrick Cavanaugh, a research engineer at Purdue’s Ray Ewry Sports Engineering Center, demonstrates how virtual cycling competitions function in a remote environment. (Purdue University photo/John Underwood)

Purdue experts aid effort to prepare virtual sport for its Olympic moment

Picture a group of Olympic cyclists nearing the final incline in a fierce race for a gold medal. As they begin their climb up the steep hill, they must apply more force with each ensuing pedal. A stiff wind blows in the cyclists’ faces, creating additional resistance they must overcome.

The competitors are neck and neck as they push toward the finish line.

However, they are also thousands of miles apart.

How can that be?

It’s possible because their sport is virtual cycling — an event in which competitors can participate from any physical location so long as they have the necessary bicycle, internet connection, software and smart trainer equipment to meet their fellow competitors on the virtual racecourse.

That hill the cyclists climbed was programmed into the race environment, with each competitor needing to exert more torque on their pedals to keep pace with counterparts racing up that same virtual hill from other points on the globe. In this immersive virtual world, everyone engages with the exact same visual imagery and conditions — including the wind resistance they faced during the climb that made pedaling more of a challenge.

Virtual cycling has rapidly gained popularity in the last several years — so much so that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the world governing body for sports cycling, Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), intend to feature it as an exhibition sport in the 2024 Paris Olympics. They believe it could become a full-fledged medal event alongside traditional cycling events in the 2028 Los Angeles Summer Games, and they selected a team of Purdue experts to help the sport achieve that eminent status.

But there remains a set of technical challenges they must first overcome, each of which relates to the same key ingredient: competitive fairness, often referred to as a “level playing field.”

Sharing Purdue expertise

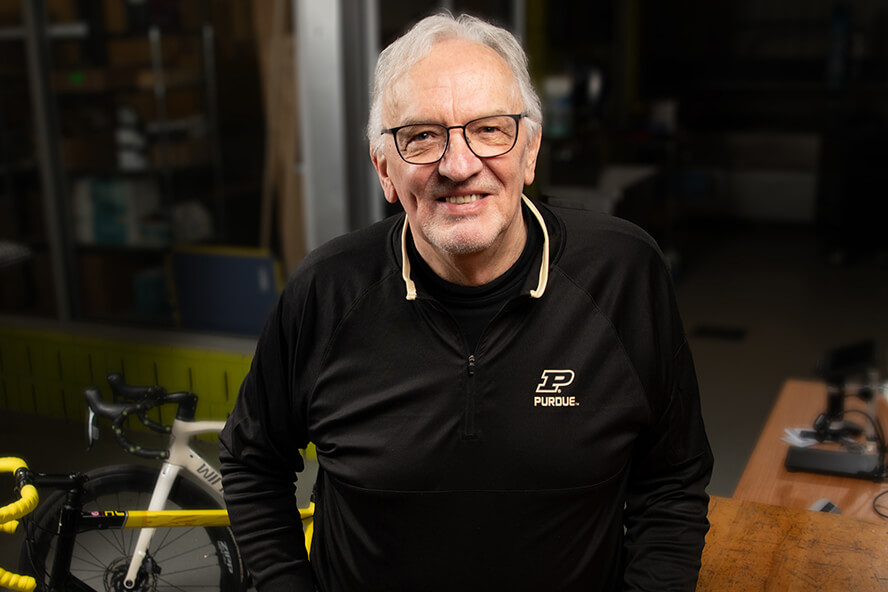

“If you don’t have a level playing field, it will never be Olympic,” explains Jan-Anders Mansson, Distinguished Professor of Materials and Chemical Engineering and executive director of Purdue’s Ray Ewry Sports Engineering Center (RESEC).

That’s where Mansson and his RESEC team have been able to help, collaborating with the IOC and cycling federation to tackle the sport’s engineering and cybersecurity issues so that the virtual competitive environment is both fair and secure.

That means building a secure network architecture able to withstand hackers’ attempts to tamper with competitors’ digital output. It also means putting the various training models on the market through a rigorous testing and certification (or homologation) process, ensuring that the systems perform comparably and meet the criteria necessary for a fair competition.

“In a traditional sport, you are competing in one environment, whether that be on a track, on the road or on a playing field. All of the participants are subject to the same environmental conditions if they’re in the same location,” says Patrick Cavanaugh (BS aeronautical and astronautical engineering ’23), a research engineer at RESEC and competitive triathlete. “However, when we bring the competition to a virtual world, the environment is no longer an objective variable. The environment has to be created by a collection of the sensor data from wherever it’s coming from.

“In this case, it’s coming from the measurement on the trainer units,” Cavanaugh says. “So if there are inaccuracies or unfairness in how that information is measured or transmitted, then you jeopardize the integrity of the competition, which is something that’s very, very unique to these hybrid sports.”

If you don’t have a level playing field, it will never be Olympic.

Jan-Anders Mansson,

executive director of Purdue’s Ray Ewry Sports Engineering Center

And by jeopardizing the competition’s integrity, you risk having it being met with indifference, both from athletes and from a viewing public whose interest is necessary to sustain the sport.

“I would imagine for the audience of the Olympic Games that integrity and fairness are the utmost important properties. Otherwise, what’s the point, right?” asks Dongyan Xu, the Samuel Conte Professor of Computer Science and director of Purdue’s Center for Education and Research in Information Assurance and Security (CERIAS), whose team enthusiastically joined the project at Mansson’s invitation. “If you have a sport where you cannot effectively detect, control, deter and hopefully eliminate e-doping or hacking, then I will lose confidence and interest.”

Luckily, the Boilermaker researchers have already made considerable headway in these efforts by creating the world’s first homologation system for virtual cycling. A RESEC team — including graduate students Teal Dowd, Diana Heflin and Justin Miller, and later Cavanaugh — created a device and methodology to evaluate smart trainer performance, with their system deducing measurement differences between some models.

“We really have to think closely about how this might affect the podium placing for a race one day,” says Dowd (BS mechanical engineering ’18), who is pursuing a PhD in materials engineering. “It makes you want to assure that the work is correct and that our accuracy in saying what trainer is good or bad is very true.”

The stakes are just as clear on the project’s data security side. Xu says the technical issues the CERIAS team faced in virtual cycling are not unusual. However, the unique domain of this particular assignment — elite competitive sports with a global audience — made this a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

“We don’t collaborate or contribute to important causes like the Olympic movement on a regular basis,” Xu says. “My colleagues and I are all excited about this opportunity and honored to contribute.”

Purdue and sports engineering

The virtual cycling project is one of several underway at RESEC, which Purdue established in 2019 as a joint effort between the College of Engineering and Purdue’s Department of Intercollegiate Athletics. Named after Purdue mechanical engineer Ray Ewry, an Olympic gold medalist in the early 20th century, the center focuses on the ever-expanding role that technology plays in sporting endeavors.

Helming the organization is Mansson, who has worked closely with the IOC and International Swimming Federation (World Aquatics, previously known as FINA) for many years in addition to his work in research and development with an America’s Cup sailing team.

Mansson’s worldwide experience with sports technology is so extensive that a crew for a Netflix documentary series, “The Future Of,” visited campus to interview Purdue faculty for an episode on the future of sports innovation.

By prioritizing excitement, integrity and safety in sports, Mansson and the RESEC team believe they can harness Purdue’s unique technical capabilities to make sports more innovative and entertaining and less dangerous.

In 2022 Purdue introduced a one-year professional master’s concentration in sports engineering, making RESEC the only U.S. university sports center with such a graduate degree program. Now Mansson plans to take advantage of Purdue’s growing presence in Indianapolis with its new urban campus there, plus RESEC’s new home in the Indianapolis headquarters of motorsports manufacturer Dallara, to build partnerships that can facilitate noteworthy sports innovation.

“During our initial three years, we managed to establish ourselves on a global level. And now we have to start to build it up in Indianapolis, which is totally exciting,” says Mansson, who is also head of the Manufacturing Design Laboratory (MDLab). “If you look at Indianapolis, it’s a main international stage. We have the (Indianapolis Motor) Speedway; we have the NCAA; we have professional teams and many of the national trials in the U.S. are held in Indianapolis. And Purdue now has a growing infrastructure in Indianapolis. It’s very natural to put an emphasis on our sports center in Indianapolis.”

Reaching new audiences

Of course, successfully shepherding a sport into Olympic competition would also bring attention to the RESEC team’s capabilities. And they appear to be well on their way toward reaching that goal.

“I don’t see that as being too far in the distant future, and that just opens the Olympic Games up to a new generation of people and a bigger audience,” said former Olympic cyclist and Tour de France stage winner Michael Rogers, now innovation manager at the international cycling federation, in a video interview with Purdue Engineering.

For Mansson, the audience engagement opportunity is one of the most exciting aspects of the project. He points out that viewers have never had more entertainment options than they do today, so sport organizers like the IOC must consistently innovate to attract audiences and young people. That’s why digitalization is such an important tool, with broadcasts presenting more and more information from the competition and athletes, in increasingly inventive ways, in an effort to captivate spectators.

This technology can also allow spectators to become competitors themselves.

Mansson pictures an Olympic virtual cycling event where riders may compete from the same physical location, but viewers also may log in from anywhere to test how their riding ability measures up against the world’s best.

I will like to see that event, knowing the work I did played a direct role in the introduction of the sport to more people and that I’ve influenced the outcome of an Olympic champion.

Teal Dowd, RESEC team member and graduate student in materials engineering

“You can imagine 100 athletes on a stage or on a podium competing on the same equipment, and in front of them they have the road and so on coming through the system,” Mansson says. “Then at the same time, you have 3 million people at home competing against them. All of a sudden, you have moved the competition of the Olympics home into the living room with that added dimension of how sport can be part of spreading well-being among people.”

The RESEC team members believe the same homologation standards they developed for virtual cycling can be applied to other virtual events like rowing or running, so we are likely on the verge of a new era of interactivity between viewers and the sports they’re watching.

The technological advances that create such interactivity will also pave the way for new sports to emerge and for new methods of staging competitions to become commonplace.

If all goes according to plan, virtual cycling will be a showcase for the emerging possibilities at the next two Summer Games — and a team of Boilermaker engineers and computer scientists will have helped it get there. “I will like to see that event, knowing the work I did played a direct role in the introduction of the sport to more people and that I’ve influenced the outcome of an Olympic champion,” Dowd says. “Personally, watching that and knowing that I contributed will be extremely rewarding.”